James Drake “Can We Know the Sound of Forgiveness” at Moody Gallery

+1

+1 James Drake “Can We Know the Sound of Forgiveness” at Moody Gallery

James Drake “Can We Know the Sound of Forgiveness” at Moody Gallery

James Drake “Can We Know the Sound of Forgiveness” at Moody Gallery

James Drake “Can We Know the Sound of Forgiveness” at Moody Gallery

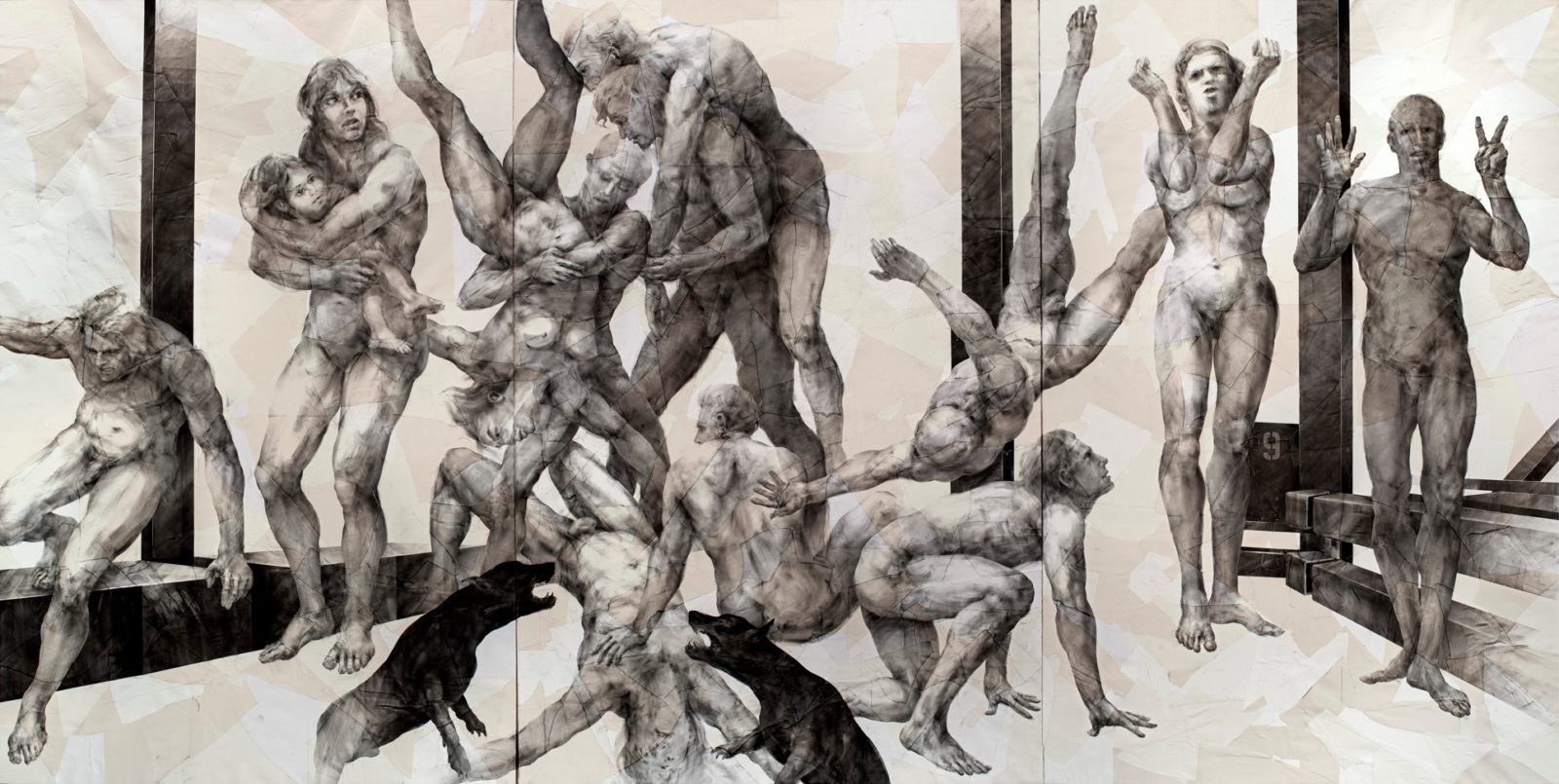

In 2005, the gurus at “Art Forum” shot a bull’s eye when they framed James Drake as a latter-day Bernini lost in the desert of the American Southwest. “Reminiscent of the Italian high Baroque in their extraordinary lushness,” is how the art mag described Drake’s charcoal drawings. When I look at Drake’s new drawings in the exhibition “Can We Know the Sound of Forgiveness” at Moody Gallery through November 20, 2021, I detect influence beyond the Baroque.

Your eye is drawn immediately to his figures’ leg muscles, particularly the bristling upper thighs. This happens before you notice distorted facial features and expressions brimming with tension. I can’t help but think Drake slurps from the same trough as Renaissance-era Tintoretto. Art historians know from biographers and from Tintoretto’s own drawings that he painstakingly copied Michelangelo’s figures. And suspended little models in the air to be reproduced with the goal of internalizing Michelangelo’s foreshortening techniques. Tintoretto’s laborious studying and borrowing underpinned his own meticulously crafted dramatic figures, defined by motion, powerful limbs and unforgettably expressive faces.

But remember, you’re not supposed to put too much emphasis on these art historical comparisons. The party line is that art-historical invocations are simplistic unvaluable elements of art critical discourse. Also looked down on, you’re not supposed to care too much about skill. Skill, the experts sniff, matters a lot less than conceptual schema.

Fancy-pants criticism however is not what we’re doing here. My sole purpose is to tell readers about James Drake’s unmitigated adeptness in handling the human figure. As far as conceptualizing goes, Drake’s art is heavily informed by themes tied to life along the U.S. Mexican border, potent content which helped nail his success. Giving visual expression to the sign language used by women to communicate with incarcerated lovers got him included in the 52nd International Venice Biennale. As for these new drawings, if I understand the gallery’s chatter, Drake created resonant allusions to the joy and misery of the human condition.

I recall years back strolling into a neighborhood cocktail thing and noticing two of Drake’s large drawings in the host’s dining room. I knew Drake had banked museum collections, the MFAH, the Whitney, Brooklyn Museum, National Gallery, Smithsonian, numerous others, but it sure was interesting to see a collector living with Drake’s art, there it hung all in-your-face and sassy right near the dining table.

This is Santa Fe-based Drake’s seventh solo exhibition at Moody Gallery. His show features a monumental twelve feet by twenty-four feet charcoal drawing mounted on canvas. Small working drawings and related sketches are also displayed.

In 2013, I had a chance to ask Drake a few questions.

VBA – Your works on paper seem heavily influenced by Renaissance and Baroque drawings. Do you look to them for inspiration?

JD -Yes, I have a very real passion for Renaissance/Baroque drawings and always succumb to their beauty, sensitivity, and grace. And yes, they are a tremendous inspiration.

VBA – Why do you work in very large size?

JD – I work in a very large scale because when I draw on that scale it is necessary to use my entire body and is very physical. Up and down ladders, arms swinging, pacing back and forth – it is all a part of the process. Also, most people think of drawing at a scale of about an average sheet of paper measuring 20”x30”, however, these large drawings are meant as finished pieces and not sketches for paintings or other works. And of course, there is a certain drama inherent in large works that I try to convey to the viewer.

In that interview, Drake told me he spent his early childhood in Guatemala, and believes his work is impacted by the time his family lived in Guatemala. “Many of the issues and works I have produced are a direct response to that experience.”

The two animals that seem to be fighting and smooching at the same time call to mind the long-eared jackasses in Goya’s “Caprichos,” meant to signify societal and political absurdities. But you’re not supposed to care about art historical comparisons.

www.moodygallery.com